This post (edited for publication) is contributed to our blog as part of a series of work produced by students for assessment within the module ‘Public International Law’. Following from last year’s blogging success, we decided to publish our students’ excellent work in this area again in this way. The module is an option in the second year of Bristol Law School’s LLB programme. It continues to be led by Associate Professor Dr Noelle Quenivet. Learning and teaching on the module was developed by Noelle to include the use of online portfolios within a partly student led curriculum. The posts in this series show the outstanding research and analytical abilities of students on our programmes. Views expressed in this blog post are those of the author only who consents to the publication.

Guest author: Nikita Isaac

In this blog post I am addressing the highly topical issue of ‘cultural genocide’ and its potential inclusion in the definition of genocide. Whilst there is no legal definition of cultural genocide, we can still consider it as falling within the definition of genocide as stated in Article 6 of the ICC Statute. Several definitions of cultural genocide have been propounded by academics, one being a ‘purposeful weakening and ultimate destruction of cultural values and practices of feared out groups’ (pp 18-19). I believe that cultural genocide is present in many situations such as Darfur. This blog post argues that it is possible to include cultural genocide in the definition of genocide.

Signature of the Genocide Convention (Source: here.)

The work of Lemkin who coined the term genocide supports my view as in his broad definition he included cultural genocide alongside physical and biological genocide. He believed that physical genocide and cultural genocide were ‘one process that could be accomplished through a variety of means’ (D Short, ‘Cultural Genocide and Indigenous Peoples: A Sociological Approach’ (2010) 14 IJHR 833, 835), whether through mass killings or coordinated actions aimed at destroying essential foundations of group life.

The resulting definition in the ICC Statute is far from what Lemkin envisioned as still today cultural genocide is unrecognised legally. The travaux préparatoires of the Genocide Convention included a section on cultural genocide which was then excluded from the final version even though it had been deemed a serious human rights violation and thought to be a stand-alone crime. It is this version, that of the Genocide Convention, that was adopted in the ICC Statute. Political factors had played a part in the exclusion of cultural genocide as the United States were against formulating criteria relating to cultural genocide given their historical relationships with indigenous peoples (L Kingston, ‘The Destruction of Identity: Cultural Genocide and Indigenous Peoples’ (2015) 14 Journal of Human Rights 63, 65). So, ‘[t]he wording of the Convention was shaped … not to criminalize their own behaviour’ (C Powell, ‘What do Genocides Kill? A Relational Conception of Genocide’ (2007) 9 Journal of Genocide Research 527, 532).

The ICC Statute preamble states that parties to the statute are ‘[c]conscious that all peoples are united by common bonds, their cultures pieced together in a shared heritage, and concerned that this delicate mosaic may be shattered at any time’. Thus, if culture is a protected interest by the states that are parties to the ICC Statute why is cultural genocide not recognised?

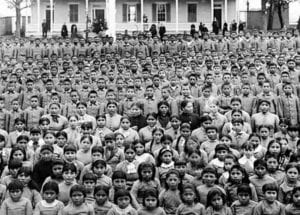

This picture shows how indigenous children were stripped of their cultural identity when forced into westernised schools. (Source: here.)

The example of what has happened to some indigenous groups in North America such as the Winnemem Wintu (see article by Kingston) substantiates my view that cultural genocide should fit within the definition of genocide. Cultural genocide affects these tribes as their culture and identity are stripped away over time and destroyed, though they may not suffer physical harm. The Winnemem Wintu are federally unrecognized (Kingston, p 70) by the US government and so are unprotected. Of the 14,000 Winnemem Wintu people only 123 remain (Kingston, p 70). They have continually lost land from the 1800s onwards (Kingston, p 70) and their cultural life as they know it is being decimated in front of their eyes. Their very means of life have been restricted through fishing bans, using plants for medicine and loss of ceremonial grounds (Kingston, p 70). The definition of genocide clearly does not safeguard indigenous people even though the loss of culture to them is just as devastating as loss of life (Kingston, p 72; see also this video). The UN Declaration of Rights for Indigenous People offers protection now, but it has taken over 60 years to reach this point and in that time indigenous people suffered detrimentally. I argue that culture can be seen as a fundamental human right. Yet, although this shows progress with regard to cultural issues, in no way does it criminalize the behaviour against indigenous people which means that there is still no international platform to criminalize cultural genocide.

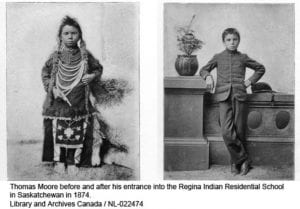

This picture displays the shocking difference before and after a child was forced into school (Source: here.)

A case which reaffirms my opinion is Prosecutor v Krstic as it dealt with the genocide of Muslim men and boys in the safe area of Srebrenica (see video). It is interesting to note that the ICTY opened the discussion of cultural genocide stating that ‘[t]he destruction of culture may serve evidentially to confirm an intent, to be gathered from other circumstances, to destroy the group, as such’ (para 53). So, it is taken that cultural destruction satisfies the test of dolus specialis needed to fulfil the mens rea of genocide. Judge Shahabuddeen dissenting acknowledged, ‘it is not convincing to say that the destruction, though effectively obliterating the group, is not genocide because the obliteration was not physical or biological’ (para 50). So, referring back to the Winnemem Wintu, although they have not physically or biologically suffered, it does not mean that they have not suffered through other means. The Winnemem Wintu have suffered through losing their culture due to the construction of a dam on their historic and sacred land. This undoubtedly reinforces the claim that cultural genocide can be recognised via case-law despite not being expressly included in the statute of an international criminal tribunal.

(Source: here.)

Overall, I truly support the idea that it is possible for cultural genocide to be included in the definition of genocide as stipulated in the ICC Statute. As discussed, originally, a much broader definition of genocide was drawn up that included cultural genocide; however, this was excluded, thereby leaving indigenous people unprotected for decades. This has had a knock-on effect in the case law which, although making obvious references to cultural issues in relation to genocide, does not recognise ‘cultural genocide’ as a crime as such.